It occurs to me how much of human communication is disambiguation.

We have short lives and shorter attention spans. So we have to be tactful about fitting in just enough detail into the brief blips of attention that we are afforded. We wouldn’t enjoy listening to protracted descriptions of things we already know. So we fast-run along a stream of concepts where we only lay down just enough track for people to keep up.

We narrate things.

We tell stories, episodic journeys with familiar names and places and little else other than dialogue and the occasional pantomime. We convey so little detail, but for the right audience, the story is as vibrant, colorful, and detailed as anything from their own sensory experiences.

Things unsaid are those that don’t need saying. The listeners know how to fill in the gaps.

Effective communication requires knowing how to balance what to say and what to leave out —either because it is a detail that is unambiguous or because it’s an intentional gap that we want the listener to fill.

Programming, at least the “classical” kind, does not afford us this luxury. Everything has to be laid out precisely and in detail; even when those irrelevant details. So we seek the comfort of layer after layer of abstraction that hides details we don’t want to see. The same abstractions alleviates us of the responsibility of saying what we don’t need to say.

We hope that, much like our human conversation partners, the computer would fill in the gaps predictably and reliably. We hope it will do what we mean, not what we said. We are disappointed, frustrated, and occasionally amused when reality surprises us.

Software is a description of a machine.

Software is only useful when something interprets it and actualizes the machine. Actualizers –a.k.a. computers– aren’t smart. Every layer of a computer system needs to be told what exactly it is supposed to do. There cannot be any guesswork. So the description of the machine must contain excruciating detail, because the computer that actuates it has no ability to fill in the blanks.

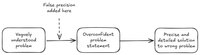

We start with a vague understanding of the problem space. But somewhere along the way, we have to inject it with false precision so that the description becomes complete.

This is why so much of modern software is based on false precision—at least when it comes to end-user-facing systems. We are forced to describe a behavior in rigid detail despite our incomplete understanding of the problem space or lack of desire to overspecify the wrong solution. The precision we inject becomes part of the solution, and in large systems, indistinguishable from pertinent details. Sadly, our descriptions of machines rarely allow us to demarcate necessary precision and unnecessary precision.

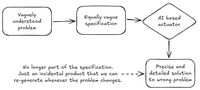

Until now, that is. Finally, we have something that can take an incomplete, vague description of our machine—stated in terms of what it does or what its effect should be on something: vibe coding.

Or to be more specific, vibe coding specifications.

Our final actuators are still brute-force stupid. But at least now we have something between us and the actuator that can fill in these pesky gaps and again allow us the luxury of ambiguity.

Ambiguity allows us to be earnest in our imperfect understanding of the problem. We didn’t understand the problem because we have no perfect understanding of the messiest, most important part of the problem—us. But now, finally, we can state our problem the way we see it: vaguely and imprecisely.